Listen to Podcast with Your Favorite Service

-

Podcast Addict

-

Breaker

-

Player FM

-

Listen Notes

- Amazon Music

-

Radio Public

By the way, if selling on-line in the United States, you have about 11,000 potential tax payments to calculate monthly or quarterly and you probably don’t know about them.

Brava! Capitalism and democracy are a nearly impossible combination….both vying for a somewhat limited amount of money. Boils down to cleverest schemes for acquiring same. Obviously mathematical training is essential. The algorithm is emperor.

Thank you for a sunny wake up.

Lynda C

Summary

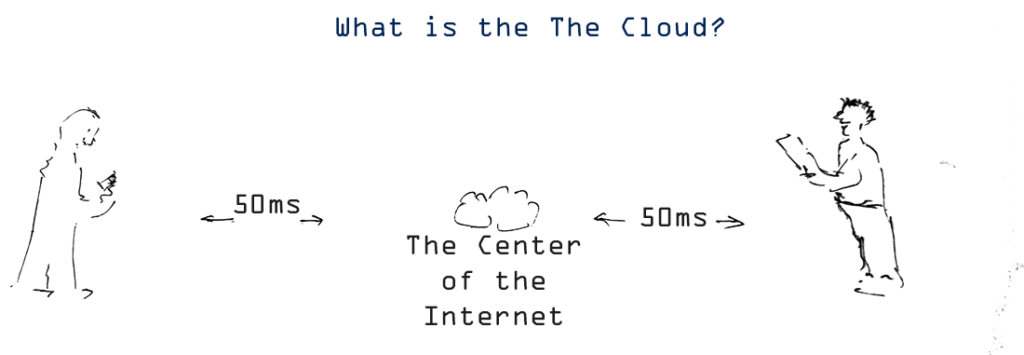

The United States Supreme Court changed the landscape of internet commerce with a 2018 ruling called “South Dakota v Wayfair Inc”. With the stroke of five pens, business had to comply with thousands of sales tax jurisdictions within the United States – up to 58 states and territories, 3,000 counties, 10s of thousands of municipalities all want revenue from internet-based sales. This determination opened businesses to new risks. It created an entirely new business venture called: interstate sales tax compliance service provider. And new phrases such as “SST” for streamlined sales tax process. It will cost small business thousands of dollars to comply. For us, compliance will cost more than the taxes we pay.

Read the episode transcript

The PDF version of transcript is here

Click Here